This is post #1 in a multi-part series on word classes and grammar theory. For updates on the next post in the series, follow us on WordPress and Facebook!

/Samuel

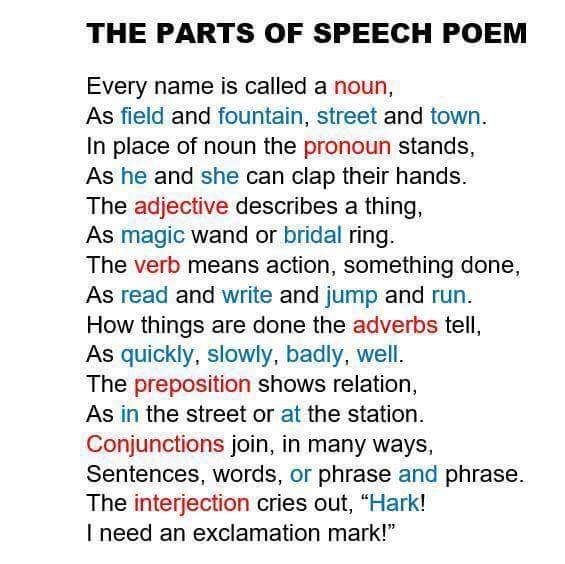

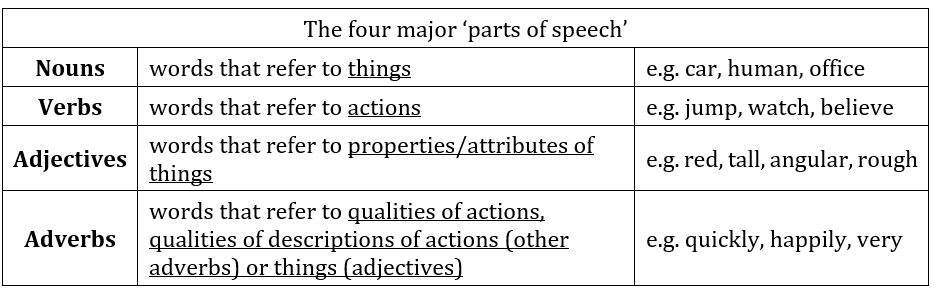

If you’ve ever attended a class on English grammar, you probably know that the vast majority of English words may be classified under at least one of four categories – nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs – based on how they broadly function in sentences and clauses.

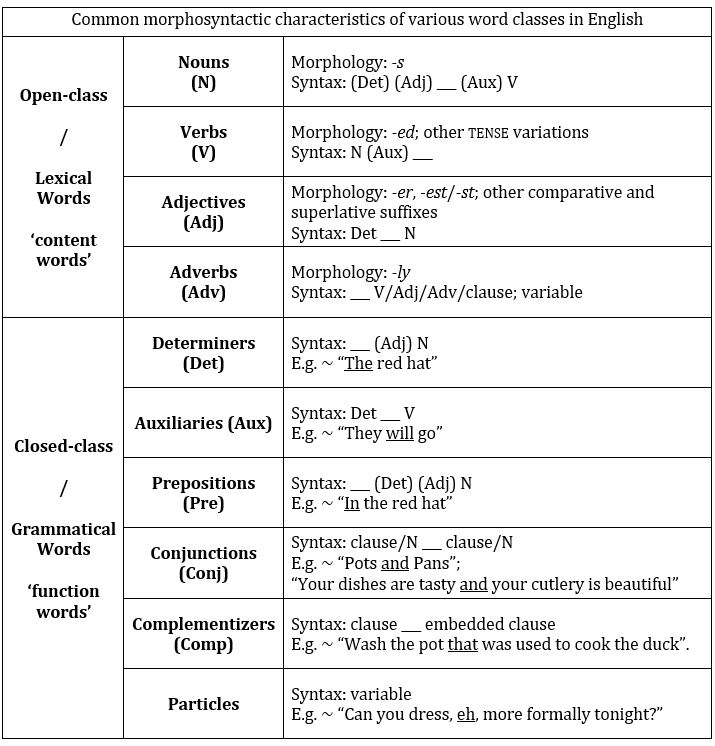

These four major categories – along with other less populated ones, such as determiners (includes articles and pronouns), auxiliaries, prepositions, conjunctions, complementizers, particles (includes interjections) – are collectively referred to as the parts of speech in traditional grammar.

You may also recall being taught that while the major parts of speech comprise ‘content words’ that specify some particular thing, action, property or quality (as detailed below), the remaining parts of speech comprise ‘function words’ that help to specify the relationships between the different ‘content words’ in a given sentence.

If all this sounds a little elementary, you might be surprised to hear that many linguists today find it problematic to use such semantic criteria – meaning or function-based differences – to distinguish between the parts of speech, due to the definitional exceptions that they produce (Jackendoff 1994; Haspelmath 2001).

Consider the nouns “explosion”, “diligence” and “fluidity”. They appear to refer respectively to: an action, an attribute of a thing (typically a person), and a quality of an action – but are not considered to be a verb, adjective, or adverb. Likewise, the verbs “know” and “lack” don’t seem to refer to any particular action. You can’t carry out an act of knowing or lacking – though you may commit an act which displays your knowledge or lack of something.

And because the definitions of adjectives and adverbs flow from those of nouns and verbs, the adjective “loud” in “a loud explosion” more properly refers to a quality of an action than a property of a thing, while the adverb “sadly” in “they sadly lacked competence” inherits similar definitional difficulties.

Why then are these ‘problematic’ words not re-categorized according to the parts of speech that more closely fit their general meaning or semantic profile? The main reason for this is that their morphosyntactic properties – the kind of variations in form these words may take (morphological variations) AND the spots these words may occupy within a sentence relative to other words (syntactic distribution) – aligns with the categories of words that they are recognized as members of. Accordingly, modern linguists tend to use the term word classes or lexical categories in place of parts of speech (and open-class/closed-class words in place of ‘content’/‘function’ words) to signal that they are referring to categories of words defined primarily by morphosyntactic than semantic criteria (Payne 1997, 2006; Cruz-Ferreira & Abraham 2011).

What then are the morphosyntactic properties displayed by these semantic oddities which validate their membership in their respective word classes? Consider again the noun “explosion”, which can be marked for NUMBER – in having both singular and plural forms – a morphological characteristic of its word class.

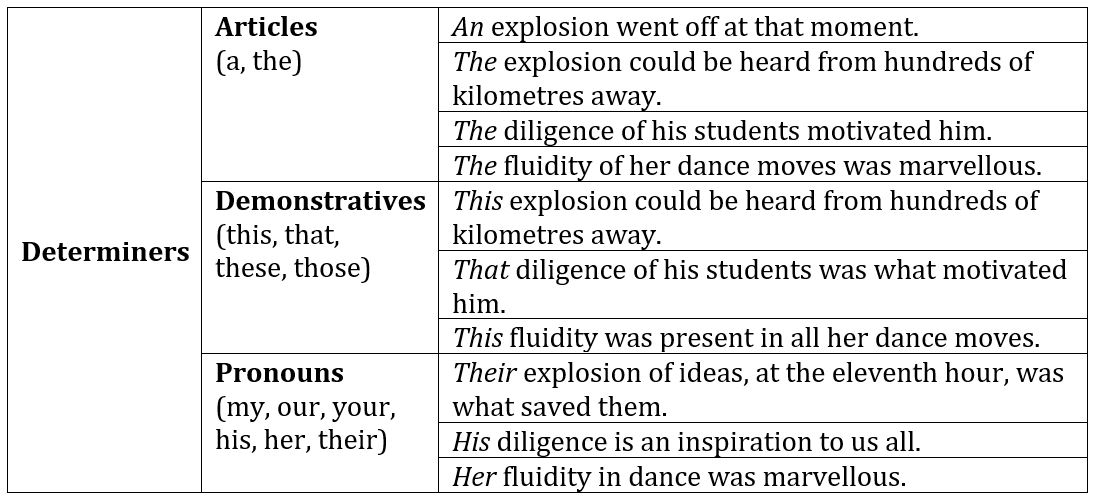

While “diligence” and “fluidity” do not share this morphological trait, all three nouns share a similar syntactic distribution – they can all occur after various determiners, a word class that marks the start of a noun phrase, which in the context of English includes such sub-classes as: articles, demonstratives and pronouns.

Likewise, the verbs “know” and “lack” exhibit morphological behaviour typical of their class, in being markable for TENSE, having both past and non-past forms. In terms of syntactic distribution, both words may come after auxiliaries, like the future-time marker “will” and hypothetical marker “would”, and nouns (e.g. “chefs”), as demonstrated in the examples below.

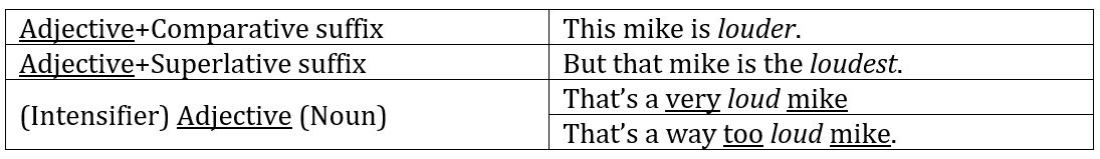

Similarly, the adjective “loud” is morphologically typical of its class in permitting the comparative and superlative suffixes – as in “loud-er” and “loud-est” – to express degree. Additionally, the ability of “loud” to precede and modify a noun like “microphone/mike”, and be preceded by an intensifier like “very” or “too”, fits with the syntactic distributions of adjectives, as shown below.

Finally, the adverb “sadly” carries the distinctive “-ly” suffix, morphologically common among many members of the class. Adverbs do not have a distinctive syntactic distribution, although unlike the three other open word classes above, they may modify whole clauses as in: “Sadly, they lacked knowledge of his wonderful cooking.” Adverbs can be thought of as the ‘leftover’ category of open-class words that do not fit the morphosyntactic criteria of nouns, verbs or adjectives.

When I first learnt about all this in my foundational courses as a linguistics undergraduate, something felt immediately wrong. Evidently, there were problems with the traditional semantic definitions of various word classes. Yet, replacing them with more ‘empirically-grounded’ morphosyntactic criteria seemed to beg the question as to why these words were displaying such morphosyntactic behaviour in the first place.

Put another way, I couldn’t escape the idea that various words displayed the morphosyntactic properties of nouns, verbs and adjectives because they functioned as nouns, verbs and adjectives in a given context, and not the other way around. And that the reason why various words functioned as nouns, verbs and adjectives was because of their categorically different (in both senses of the word) contributions to the meaning of the sentences which they appeared in.

Was my insistence of a semantic characterization of word classes merely the unfortunate result of years of conditioning in traditional grammar?

This is post #1 in a multi-part series on word classes and grammar theory. For updates on the next post in the series, follow us on WordPress and Facebook!

References

Cruz-Ferreira, M. & Abraham, S.A. (2011) The Language of Language: A Linguistics Course for Starters. Singapore: The Authors.

Haspelmath, M. (2001) Word Classes and Parts of Speech. In Paul B. Baltes & Neil J. Smelser (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. (pp. 16538–16545). Amsterdam: Pergamon.

Jackendoff, R. (1994). Patterns in the Mind: Language and Human Nature. New York: Basic Books.

Payne, T.E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Payne, T.E. (2006). Exploring Language Structure: A Student’s Guide. New York: Cambridge University Press.